The 2022 State Water Plan Water Planning Updates Reveal What's Next for Water in Texas

Texans are growing in number and for good reasons. But population growth in Texas brings higher demand for one of the state’s most precious resources — water. Ensuring our state’s finite water supplies meet future demand requires strategic planning and collaborative efforts from Texas citizens and every level of government.

Mansfield Dam on Lake Travis, near Austin, Texas

Statewide water planning, in fact, is far from a foreign concept in Texas. Texans are all too familiar with massive floods and severe droughts. Despite facing challenges, Texas is uniquely positioned to lead the nation in water planning and conservation.

Water Planning in Texas: A History

Since its inception in 1957, the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) has been a steward of Texas water. The mission of the TWDB — “to lead the state’s efforts in ensuring a secure water future for Texas and its citizens” — may sound simple, but the complexity of Texas’ diverse population and environment guarantees it is no easy task.

The drought of the 1950s changed Texas and its water policy forever. Persisting for the better part of the decade, from 1950 to 1957 (PDF), the drought cost Texas agriculture producers nearly $39.8 billion (in 2021 dollars) in direct losses and damaged more than 4 million acres, the result of wind erosion and wildfires. Born out of a legislative response to the drought’s devastation, one of TWDB’s core objectives is to keep Texans from being unprepared for another drought of record.

While the functions of TWDB have evolved over the decades, Senate Bill 1 passed by the 75th Legislature in 1997 catapulted the agency into a statewide leadership role overseeing the formerly decentralized regional water planning efforts. TWDB’s compact with Texans lists the agency’s core responsibilities as: collecting and disseminating water-related data, planning for the development of the state’s water resources and administering cost-effective financing for water planning programs.

Planning for the State's Water Reality

Integral to Texas’ water supply is TWDB’s State Water Plan (SWP). The SWP is a five-year water planning guide for state water policy designed to anticipate and plan for the water needs of Texas based on conditions similar to the most recent drought of record. The SWP seeks to plan for the state’s water needs 50 years into the future.

Todd Votteler, president of Collaborative Water Resolution LLC, which helps clients mediate water conflicts, says that one of the state’s biggest challenges is “meeting the water demands of a rapidly growing state that is subject to intense multiyear droughts, where the populations are not always located proximate to the available supplies of water.”

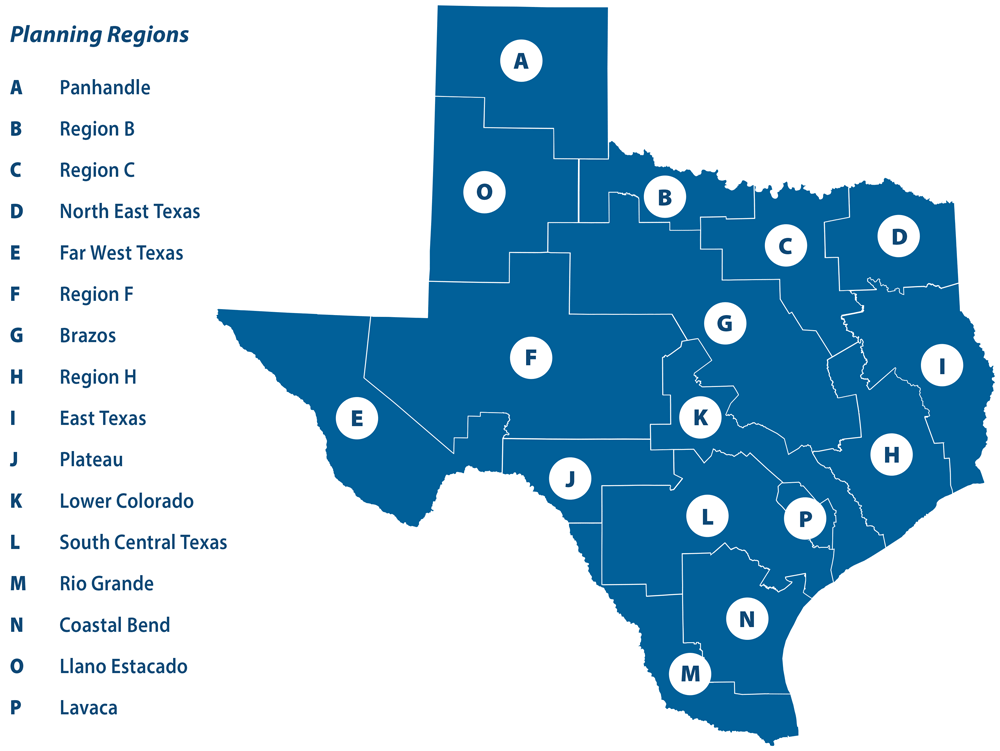

Texas is divided into 16 water planning regions, each with its own unique set of water needs (Exhibit 1). Every five years an updated SWP is released that details water supply, demand and needs for various water user groups, including municipal, irrigation, manufacturing, livestock, mining and steam-electric power. The SWP serves as both a guide for Texas water policy and a metric for regional water supplies and needs. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality also plays a role in the planning process as the regulatory body for environmental issues in Texas.

Exhibit 1: TEXAS WATER PLANNING REGIONS

Source: TWDB

- A: Panhandle

- B: Region B

- C; Region C

- D; North East Texas

- E: Far West Texas

- F: Region F

- G: Brazos

- H: Region H

- I: East Texas

- J: Plateau

- K: Lower Colorado

- L: South Central Texas

- M: Rio Grande

- N: Coastal Bend

- O: Llano Estacado

- P: Lavaca

Cybersecurity for Water Utilities

Recent events in Ukraine have stoked fears about large-scale Russian cyberattacks against the U.S. Experts say that vulnerable targets include water utilities that depend heavily on computer systems to operate. According to the PEW Charitable Trusts, there are about 52,000 community water utilities in the U.S., most of which are operated by local governments and private companies that lack adequate funding to implement cybersecure systems. Water and wastewater systems represent one of 16 “critical infrastructure” sectors that, if disrupted, could have disastrous effects on national security, public health and economic growth.

The Environmental Protection Agency warns that cyberattacks on this sector not only have the potential to affect business processes (e.g., stolen customer financial data), but they also can be physically destructive to water facilities and harmful to households. Cybercriminals have shown they can manipulate operations at water treatment plants, such as disabling pumps and overriding alarms, which could then lead to water contamination and shortages.

In February 2021, cybercriminals hacked into the computer system at a water treatment facility near Tampa, Florida, that serves about 15,000 people and attempted to increase the amount of a certain chemical in the water supply to dangerous levels.

The TWDB has addressed cybersecurity in its agencywide strategic plan.

Sources: U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency; Environmental Protection Agency; Reuters; SWP

Water Planning is a Group Effort

Though TWDB bears the ultimate responsibility for developing the SWP, the participation of all 16 regional water groups makes the plan comprehensive and representative of the state’s diverse needs. Regional water planning groups are composed of both voting and nonvoting stakeholders, including members of the public, small business owners, river authorities, municipalities and environmental and agricultural interest groups.

Each group develops and submits a region-specific plan utilizing its own data, along with population, water supply and water demand data sourced from TWDB. Exhibit 2 shows the projected population and water demand data for each region.

Each regional water planning group develops the water supply plan for its planning area using state funds administered by TWDB. These plans identify water supply projects and strategies to address future needs.

Exhibit 2: PROJECTED POPULATION GROWTH AND CHANGE IN DEMAND* BY WATER PLANNING REGION, 2020-2070

Projected Population Grown by Water Planning Region

- Region A: 52%

- Region B: 11%

- Region C: 92%

- Region D: 65%

- Region E: 63%

- Region F: 45%

- Region G: 84%

- Region H: 60%

- Region I: 35%

- Region J: 31%

- Region K: 87%

- Region L: 73%

- Region M: 105%

- Region N: 21%

- Region O: 49%

- Region P: 12%

- Texas: 73%

Projected Water Demand Change by Water Planning Region

- Region A: -25%

- Region B: -1%

- Region C: 67%

- Region D: 19%

- Region E: 17%

- Region F: -3%

- Region G: 27%

- Region H: 32%

- Region I: 14%

- Region J: 16%

- Region K: 17%

- Region L: 26%

- Region M: 4%

- Region N: 9%

- Region O: -27%

- Region P: -1%

- Texas: 9%

*Reduction in demand is projected to come from agricultural, municipal and other conservation efforts.

Source: TWDB

Walt Sears, executive director of the Northeast Texas Municipal Water District in Region D, describes TWDB as an essential and “extremely valuable source of funding and comprehensive planning” vital to the conservation of water in Texas. He says social, economic and industry growth, coupled with a rapidly growing population, are all important factors in driving regional water groups to plan for Texas’ current and future water needs.

Economic Impacts

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of water to the economy. Prominent industries across Texas and the nation, such as agriculture, mining, manufacturing and health care depend on clean and reliable water sources to operate. Clean water for households and businesses also promotes public health, a prerequisite for economic growth.

Since 1997, Texas law requires the state’s regional planning groups to assess the economic and social costs of not meeting their water needs. Most planning groups request TWDB to conduct the analyses for them — this is where TWDB’s projections and socioeconomic analysis team comes in. The team uses IMPLAN software, among other techniques, to produce estimates of the economic and demographic impacts of a one-year repeat of the region’s “drought of record.” The estimates assume that no strategies have been implemented to reduce water needs, and therefore, evaluate worst-case potential shortages.

Many planning regions have identified theoretically worse droughts of record for their water supply analyses than the 1950s drought that has often been used as the benchmark. For many water demand projections in the current water plan, the more recent drought of 2011 represents the driest year on record.

“The analysis gives us a first pass examination of those possible costs if we don’t do anything [about water needs],” says John Ellis, TWDB’s economist. “It helps point out those regions and cities that are probably going to face some significant adverse impacts in the future, and it gives a bit of an anticipated timeline for that.

“Our analysis focuses on two measures. One is lost income or lost value added, which also represents an estimate of GDP for each of the individual planning regions. The other is lost jobs.”

Ellis says that his team also estimates several secondary impacts, including forgone tax collections, school enrollment losses and population losses. Exhibit 3 shows the projected statewide losses in income, jobs and population if planning groups take no action to reduce their water needs. Ellis stresses, however, that these data most likely underestimate monetary losses and overestimate job and population losses when viewed from a state-level perspective.

Exhibit 3: PROJECTED STATEWIDE ANNUAL ECONOMIC AND DEMOGRAPHIC IMPACTS IF WATER NEEDS ARE NOT MET, 2020-2070

| Loss | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 | 2070 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income loss (in billions)* | $110 | $128 | $128 | $132 | $140 | $153 |

| Job loss | $615,000 | $785,000 | $883,000 | $1,019,000 | $1,179,000 | $1,371,000 |

| Population loss | $113,000 | $144,000 | $162,000 | $187,000 | $217,000 | $252,000 |

Notes: Results are the summed impact estimates for the 16 planning regions in Texas; the impact model requires making many assumptions and acknowledging the model’s uncertainty and limitations, including a lack of reliable water use data for portions of the economy and limited knowledge concerning how a given economic sector might respond to a long-term drought; combining data for all regions may underestimate the economic impacts.

Source: TWDB

“Our analysis is redone every five years, and we are constantly updating our methodology as well as the data we use to make projections,” says Ellis. “By doing so, it keeps this critical issue before the public and the Legislature. Especially as Texas continues to grow, [water planning] will become a bigger and bigger issue.”

Water Project Funding

Water projects typically require large initial investments, or capital costs, followed by decades-long payback periods. TWDB estimates that implementing the water projects recommended by the regional planning groups in the 2022 SWP will require $80 billion in capital costs over the next 50 years — and the agency expects $47 billion of that to come from state financial assistance programs (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: REPORTED STATE FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE NEEDS BY DECADE, 2020-2070

| Cost Category | 2020-2029 | 2030-2039 | 2040-2049 | 2050-2059 | 2060-2069 | 2070-2079 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning, Design, Permitting and Acquisition Funding | $4.5 billion | $3.4 billion | $1.4 billion | $0.7 billion | $0.2 billion | $0.1 billion |

| Construction Funding | $13.8 billion | $8.0 billion | $7.5 billion | $3.1 billion | $3.3 billion | $1.0 billion |

| Total State Financial Assistance Needs | $18.3 billion | $11.4 billion | $8.9 billion | $3.8 billion | $3.5 billion | $1.1 billion |

Source: TWDB

“The majority of these major [water] projects are for the long haul,” says Sears. “When we’re talking about a 50-year [planning] horizon for these projects, you have to talk about people that haven’t even been born yet.” He explains that TWDB provides long-term financing for high-cost water projects with a repayment method that allows the costs to be shared years into the future.

The largest state funding mechanism is the State Water Implementation Fund for Texas (SWIFT), a financial assistance program for water projects designed to conserve existing water supplies and create additional water supplies. (The Texas Treasury Safekeeping Trust Company manages these funds.) SWIFT provides project sponsors (e.g., municipalities, counties, river authorities) low-cost financing options for water projects recommended in the SWP that require long-term borrowing. These projects often involve the construction of new infrastructure; however, some projects involve planning, design and/or acquisition without any construction.

SWIFT has committed nearly $9.2 billion in financial assistance for 58 recommended state water plan projects since 2015, the program’s first year. Sears says that while funding initiatives by the federal government, like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed last year, are helpful in the short term, it is SWIFT and other funding programs administered by TWDB that do the “heavy lifting.”

“We would not be having success in the 21st century if SWIFT had not come along,” he says. “It was a critically important decision made by state legislators and voters that we are still hugely benefiting from.”

Conclusion

“The water planning process has encouraged Texas to consider its future needs as our state grows and to some extent prepare for that growth,” says Votteler.

No doubt preparing Texans for drought will continue to present challenges and require advancements in water planning to adapt to those challenges. FN

To learn more about water infrastructure financing in Texas, see our April 2019 edition of Fiscal Notes.

You also can read about cybersecurity and efforts in Texas to defend against cyberattacks in our December/January 2022 edition of Fiscal Notes.