Helping Foster Youths in Higher Education Texas Programs Assist Vulnerable Kids

As this issue went to press, the coronavirus was sweeping our state and the nation. The consequent shutdowns are having obvious impacts on Texas government and the state’s economy; the Comptroller’s office is monitoring the situation closely. Our May-June issue will begin the discussion.

According to the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS), more than 33,000 Texas children and youths were placed in foster care in fiscal 2019, and during that year more than 51,000 were under DFPS care at some point. These kids represent a vulnerable subset of Texas’ large and growing adolescent population. Those who experience abuse and neglect in childhood often are left with lifelong scars, physical and emotional, and many face difficulties in making a successful transition to adulthood.

Foster care is intended to protect children who can’t safely live at home with their parents, generally because of abuse or neglect. In Texas, such youths are placed in the state’s foster care system when a relative or family friend can’t provide care. Texas courts grant DFPS temporary legal custody, called conservatorship, of these youths.

The social and economic consequences of children in turmoil are dramatic. Students who have been in foster care complete high school, college and vocational training at much lower rates than their counterparts. Texas’ economic progress will depend on how well the state can ensure educational success for all its young people — including the most vulnerable.

Leaving Foster Care

In Texas, DFPS conservatorship of a youth ends when “permanency” is achieved through family reunification, adoption or custody to relatives, or when the youth turns 18 — “aging out” — whichever comes first. More than 20,300 youths left DFPS conservatorship in fiscal 2019; of those, 93 percent achieved permanency of some kind, and 6 percent aged out.

Nearly 19,000 youths who achieved permanency in fiscal 2019 spent an average of about 1.5 years in care with two placements each. Those who aged out in that year, however, spent an average of nearly four years in care and experienced more than six placements (Exhibit 1).

Regardless of how these youths leave care, the abuse and neglect that initiated their placement in foster care puts them at a high risk of emotional and behavioral problems that can adversely affect educational attainment.

Exhibit 1: Youths Exiting DFPS Conservatorship in Texas, Fiscal 2019

| Exit Reason | Average Months in Care | Average Placements per Exit | Number of Exits | Share of Total Exits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achieved Permanency | 17.7 | 2.1 | 18,909 | 93.0% |

| Family Reunification | 12.8 | 1.9 | 6,739 | 33.1 |

| Custody to Relatives | 14.7 | 1.9 | 6,063 | 29.8 |

| Adoption | 26.2 | 2.4 | 6,107 | 30.0 |

| Aged Out | 44.8 | 6.3 | 1,212 | 6.0 |

| Other* | 13.3 | 1.7 | 222 | 1.1 |

| Total | 19.3 | 2.3 | 20,343 | 100.0% |

*Missing or incomplete data.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services

An Educational Challenge

Compared to their peers, students in foster care are 3.4 times more likely to be suspended from school and 3.6 times more likely to drop out of high school, according to data presented at the 2017 P-16 Statewide Professional Development Conference (PDF). Although DFPS always seeks to place youths in foster care in a safe and permanent living arrangement as quickly as possible, many are moved from home to home multiple times until an appropriate living arrangement can be established.

Multiple moves often involve changing schools, another factor that can affect student performance; foster students can lose valuable social supports and even course credits. According to data presented at the 2017 conference, 47 percent of Texas students in foster care have attended at least two different schools in the same school year, versus just 7 percent of students not in care.

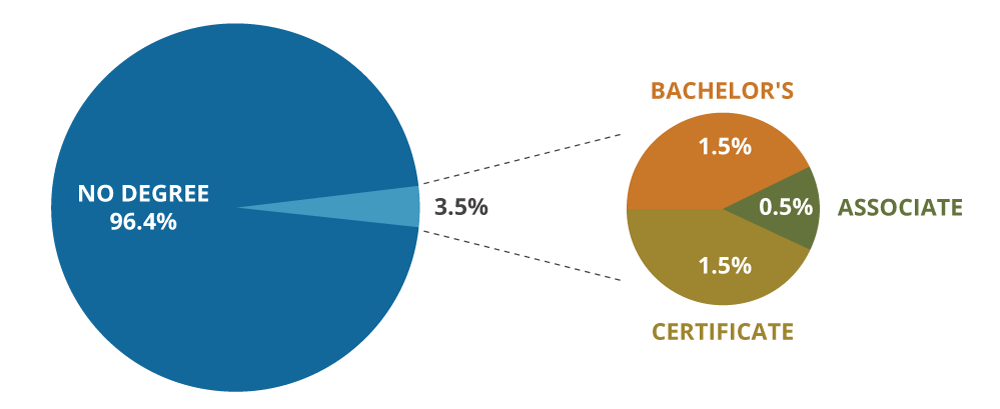

For those who have left foster care, postsecondary education can be challenging simply because they haven’t had the same level of familial and financial support as their peers. In a 2017 study (PDF) of nearly 4,000 former Texas foster-care children, two-thirds (67 percent) hadn’t pursued postsecondary education. Of those who did enroll, fewer than 4 percent had earned a certificate, an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree (Exhibit 2).

In the 2017 study, 38 percent of nearly 4,000 youths aged out of foster care after turning 18, while 62 percent left foster care after achieving some sort of permanency. The results suggest that foster-care alumni struggle educationally regardless of exit reason, age or time spent in DFPS conservatorship.

Exhibit 2: Attainment of Texas Foster-Care Alumni Pursuing Higher Education, Ages 18 to 24

- No Degree: 96.4%

- Certificate: 1.5%

- Associate: 0.5%

- Bachelor: 1.5%

Note: Study cohort consisted of 3,855 persons formerly in foster care who turned 18 between Sept. 1, 2008, and Aug. 31, 2009; the length of time in foster care and each individual’s tuition waiver eligibility are unknown. Totals may not add due to rounding.

Source: Education Reach for Texans

Liaisons for Higher Education

Texas lawmakers have established programs to help address low college enrollment and retention rates among foster-care alumni. In 2015, the Legislature amended the Education Code to require each Texas public institution of higher education (IHE) to appoint at least one employee to serve as a foster-care liaison.

These liaisons help identify those who have been in foster care and provide them with a direct point of contact with the school from enrollment to graduation. They’re also responsible for disseminating information about available support services and financial resources. According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (PDF) (THECB), about 117 liaisons serve foster-care alumni at Texas universities, state colleges, community colleges, technical colleges and health-related institutions.

Dr. Javier Flores, foster-care liaison at Angelo State University, says that “navigating through the higher education admissions and enrollment processes can be daunting, especially for individuals formerly placed in foster care.” In his role as vice president for student affairs and enrollment management, Flores works with “departments across the university to develop processes, practices and programs leading to an increase in enrollment, retention and ultimately graduation rates” for former foster kids.

Tuition and Fee Waivers for Foster Kids

Texas is one of 22 states that provides a college tuition waiver program for youths and young adults currently or formerly in foster care. Texas’ program, established by the Legislature in 1993, waives tuition and required fees (excluding optional fees such as parking costs) at state IHEs for young people currently or formerly in DFPS’ foster care program. To qualify, participants must enroll in an IHE as an undergraduate student or in a dual-credit course by age 25, among other requirements. The tuition waiver is an unfunded mandate, meaning that state-supported IHEs must cover the associated loss of tuition and fees without reimbursement from the state.

A 2018 study conducted by faculty from several state IHEs, including Texas State University in San Marcos, suggests that those who have been in foster care and use the state college tuition waiver have higher rates of first- and second-year retention, higher grade-point averages and higher graduation rates than those who don’t. The study also found that youths who use the waiver are about three times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree than those who don’t. Data compiled by THECB, however, show that waiver use among eligible foster youths is limited. Of the 1,666 eligible foster children born in 1992 who were tracked through the 2015-16 academic year, only about 25 percent used the waiver.

Some signs point toward greater use of the waiver, however. In fiscal 2018, a total of 6,037 Texans received tuition and fee exemptions under the tuition waiver program. Of these, nearly 59 percent (3,547) were currently or formerly under DFPS conservatorship, while about 31 percent (2,490) had been adopted. Use of the exemption rose from the previous year for both groups — by 6.6 percent and 16.7 percent, respectively (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Foster and Adopted Youths Receiving State College Tuition Wavers in Texas, Fiscal 2017 and 2018

| FY 2017 | FY 2018 | Percent Increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current/former youth under DFPS conservatorship | 3,328 | 3,547 | 6.6% |

| Adopted youth | 2,134 | 2,490 | 16.7% |

Note: Data self-reported by institutions of higher education.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services

Fiscal 2018 exemptions for those currently or formerly in foster care or who were adopted from DFPS foster care amounted to $22.2 million in foregone tuition and fee revenue. Community colleges served the highest number of young adults receiving tuition waivers in fiscal 2018; about two-thirds of those receiving tuition waivers (4,015) attended community colleges. Nearly 70 percent ($15.4 million) of the cost, however, was assumed by universities, which have considerably higher tuition rates (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: Number of Students Currently/Formerly in Foster Care Receiving Tuition Waivers and Value of Waivers by Type of Institution, Fiscal 2018

| In Foster Care | Adopted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Institution | Number of Students | Value of Waivers | Number of Students | Value of Waivers |

| Public Universities | 834 | $6,238,596 | 1,041 | $9,153,645 |

| Community Colleges | 2,601 | $4,135,459 | 1,414 | $2,212,710 |

| Public Health-Related | 6 | $40,844 | 9 | $67,310 |

| State Colleges | 33 | $101,848 | 26 | $60,873 |

| Technical Colleges | 73 | $180,091 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 3,547 | $10,696,838 | 2,490 | $11,494,538 |

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services

Transitional Living Services

DFPS promotes self-sufficiency and success among foster-care alumni through its Transitional Living Services (TLS) programs, provided by DFPS staff, contracted service providers and 18 transition centers across the state. The state college tuition and fee waiver is one of these programs, but it’s not the only one. Other TLS programs include:

- Circles of Support — voluntary support group meetings that include foster youths, family members, foster care providers and teachers to help develop and review transition plans for entering adulthood;

- Preparation for Adult Living — a program preparing older foster youths for a successful transition to adulthood with resources such as life skills training, transitional living allowances, case management, aftercare room and board assistance, GED classes and driver education; and

- Education and Training Vouchers — a federally funded program that provides eligible youths with up to $5,000 per year to attend college or vocational training.

Supervised Independent Living

DFPS also administers Supervised Independent Living (SIL), a type of extended foster-care placement that allows young adults aged 18 or older to reside in a less restrictive living arrangement while continuing to receive casework and support services to help them become self-sufficient. It also connects participants to higher education. Extending foster care beyond age 18 is very beneficial for those aging out of the system. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, extended foster care doubles the likelihood they will complete at least one year of college by age 21.

“As with any youth turning 18,” says Debra Emerson, DFPS’ CPS director of Youth Transitional Living Services, “many are not prepared to be fully independent. Extended foster care provides the same support parents provide their own children for successful transition to adulthood.”

SIL provides those currently or formerly in foster care with an extra layer of support to reduce the stress of living independently for the first time. Young adults in SIL programs live independently in college dorms, where they are immersed in academic and social life on or near campus and receive financial help for necessary purchases. According to Education Reach for Texans, transitioning directly from foster care to student housing can increase the likelihood of attending and committing to higher education. Currently, 13 SIL sites operate at IHEs across Texas, including two community colleges (Exhibit 5); the newest site is Texas A&M at College Station.

Exhibit 5: Supervised Independent Living Contracted Providers

| Name of Institution | Type of Institution | Comptroller Region |

|---|---|---|

| Texas Woman's University | University | Metroplex |

| University of North Texas | University | Metroplex |

| Tarleton State University | University | Metroplex |

| Weatherford College | Community College | Metroplex |

| Navarro College | Community College | Metroplex |

| West Texas A&M University | University | High Plains |

| Texas Southern University | University | Gulf Coast |

| Texas A&M - San Antonio | University | Alamo |

| University of Texas at San Antonio | University | Alamo |

| Texas A&M - Corpus Christi | University | South Texas |

| Texas A&M - Kingsville | University | South Texas |

| Texas A&M - International University | University | South Texas |

| Texas A&M - College Station | University | Central Texas |

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services

University Programs

In addition to state-level support, programs at some universities around the state provide helpful resources for foster-care alumni seeking postsecondary degrees.

Texas State University, for instance, established its Foster Care Alumni Creating Educational Success (FACES) program in 2011. With a network of more than 50 mentors and access to university and community resources, FACES aims to increase the retention and graduation rates among foster-care alumni attending the university. FACES students can access mentoring services from Texas State faculty and staff, a lending library providing free textbooks and emergency funding for necessary expenditures such as rent or medical services.

Similarly, in 2019 the University of Houston (UH) launched the Diamond Family Scholars Program with a $17 million endowment from local philanthropists. With a wide range of support services, notably an $8,500 annual scholarship, the program intends to increase the current four-year graduation rate of foster-care alumni at UH from 37 percent to 60 percent within four years, with a long-term goal of 80 percent.

Texas’ current and former foster youths are at a high risk of poor educational outcomes that can damage their prospects for economic success and a better life. Texas has taken meaningful steps to help them succeed — and build a strong future workforce that includes all Texans. FN

For more information about how some young Texans are financing their higher education goals, see our article on student loan debt in our March issue.